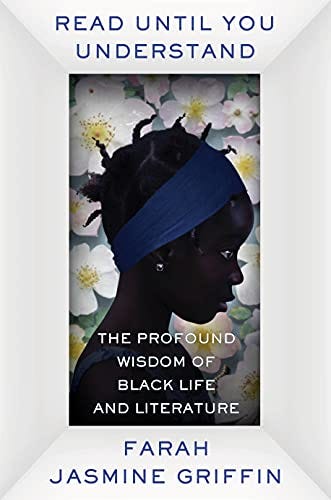

Memoirs stand apart from biographies, by opening us up to how an individual documents the inexorable pull that family, friends, and memory have on them. For Black people, the memoir can be a way to explicate the soul, tenderly, especially as we try to render ourselves beyond the mere footnotes of history. I recently finished Read Until You Understand, a literary historical memoir by Dr. Farah Jasmine Griffin. Dr. Griffin is an American academic and professor specializing in African-American literature. Born in 1963 Pennsylvania, Professor Griffin grew up poor in the segregated city of Philadelphia. Her mother, Mena, worked in garment factories, while her father, with the assistance of the GI bill, was able to get a degree in Architectural Engineering from Temple University. Eventually he worked for the post office. At times, reading the text felt like looking into a mirror, but at other times, I knew it was a particular Black American story that could resonate with everyone.

As I navigated through Read Until You Understand, I saw how Griffin was immersed in the Black radical reading tradition, imprinted by her father, her mother, and the intergenerational community who instilled in her the will to find inspiration on the page. She explores familiar themes such as the Great Migration, Jim Crow, and the Civil Rights Movement, but these events, and her scholarship, are not a bookend to US history’s relic but how reading helped her through grief. Speaking on the death of father during her childhood, Griffin asks: How do we recover from grief through reading? She looks to authors like Haitian-America writer Edwidge Danticat, who in The Art of Death, who proclaims, “death is not the end.”

For me, Read Until You Understand carries a torch for the Black working class who find beauty in the hair salon, in each other’s houses, at the dance hall. The book’s strength comes from its bibliography as much as it comes from the voice, especially when Griffin exalts the greats from James Baldwin to Lorraine Hansberry. At times, she weaves through their didactic syntax, which can feel heavy, but at other times, the eye drifts across poetic rifts and raw prose. The book is most poignant when the author brings us to her family and is enlivened by her love for Black people.

The text is an invitation to dive into the expansive world of Black literature. She is drawing from Richard Wright’s Native Son, Ernest Gaines’s A Lesson before Dying, and Tayari Jones’s An American Marriage—monographs that on the surface unveil “the ultimate crime is to be have been born Black in America.” Of course, we should ask: who considers this to be a crime? Griffin’s cases are diverse and compelling, a tacit mandate that we should all be doing more reading. Moving away from circumscription, Griffin gives us space to transport ourselves from Black literature to her memoir. She notes:

As a form, the novel can raise questions about the possibilities and goals of justice. It allows us to imagine what a society governed by an ethic of care, a society devoted to restoring and repairing those who have been harmed, giving them the space for transformation, might look like.

The pervasive and invasive practice of forced sterilization could be found in such novels as Toni Morrison’s Home, but community repair, the healing of emotional scars, according to Griffin, was fund in the community of women who provided for each other, and who in real life, could shift the language of reproductive rights. Indeed, one of the benefits of being African American might be the license to feel in community. Pushing the boundaries of memoir and tradition, she also notes that writers such as Toni Morrison "never turns away from the harsh realities of Black life." I agree. In a way, we must face the pain and the glory so that we have a chance to greet the sublime. Griffin is trying to answer large questions about what it means to be Black in America. bringing us to a chapter on grace which notes:

Even under slavery and the conditions of captivity that follow its formal end, the human longs for beauty and seeks grace. For Black people, grace most often manifests in momentary bits of freedom for which we still struggle.

In a way, she makes a case for Black endurance, but more importantly, our perennial quest for emancipation. The timbre of Griffin’s work is interlaced with grief and joy, unburdened by trauma, but the necessity for engaging in a robust re-reading. The bold and the propitious (re)read.

Reading List

The long journey to Black freedom is part of a literary tradition where we acknowledge our living and dead ancestors, while also fashioning our story as we want it. These are some (family) memoirs that speak to the ways we actively express ourselves. The Black memoir is lit and this list is not exhaustive but fresh on my mind.

Michael Arceneaux| I don’t want to die poor

Sarah M. Broom | The Yellow House

Bernardine Evaristo | Manifesto: On Never Giving Up

Ashley C. Ford | Somebody’s Daughter: A Memoir

Saeed Jones | How We Fight for Our Lives

Kiese Laymon | Heavy: An American Memoir

Jesmyn Ward | Men We Reaped: A Memoir