Last month, I gave birth to a child. Like my mother, grandmother, and her mother, I grew a new kidney, a pair of lungs, and ribs in my womb not knowing what to expect. Given my long and arduous experience with IVF, I spent months wondering and worrying, unsure of who to tell about the pregnancy and whether the pregnancy would come to term. As my belly grew, I was more assured that I would be a parent, a simultaneously exciting, surreal, and scary prospect. The alarming part had more to do with my anxiety about whether or not I can continue the life I have built for myself rather than whether I will be a “good” mother. I read memoirs about motherhood, re-oriented myself to feminist literature, and spoke with other expectant mothers in Berlin. I also traveled through my home state with a belly bump, interviewing people about abortion access in Florida. I connected with cousins and talked about family secrets and recipes. Pregnancy became comforting because a community held me.

But that reassurance also came with doubt. As an American writer living in Germany, I considered how my motherhood might hinder or shape my creative process, social relationships, and time. Even though Germany provides some benefits, women still experience physical limitations during gestation, breastfeeding, and childrearing. But there is something else that I think about, especially when I speak with some of my friends who are young(ish) mothers living in Germany. I am aware of how uneven the childcare obligations are—even with their progressive male partners. Women often pick up their children from Kita (nursery school), work part-time, and party less. For most of these women, these social differences are eclipsed when they reflect on their love for their children or what they learn from seeing their young children smile for the first time. I don’t deny that these are beautiful perks that shape why people have families and are part of why I am selfishly starting a family against the ongoing climate crisis.

I know how to love deeply. In my marriage, I am prone to giving my partner small gifts and sending him poetry, kissing passionately and tapping his bum in public. These acts come organically because I adore my partner. Unlike many Europeans I encounter, he has a great sense of humour that doesn’t involve mocking marginalized people or being mean. He’s caring and cries every time we watch a romantic comedy film and loves to eat flavorful food just as much as I do. Living in Berlin, his compassion—which I love—overshadows the cynicism I encounter in academic or literary circles. My desire to marry him is possibly attributed to so many other people not measuring up to him.

Nevertheless, my union has become materially necessary after four years of marriage. And this is where the class issue comes into play. Over the past few years, there has been a cost-of-living crisis, a rise in housing costs in the city, and the war in Ukraine 1400 kilometres away, which have led to a new wave of refugees. (Since the start of the war, my partner and I have temporarily housed four displaced people.) Living with my partner at this moment has taught me that life as a person with working-class roots is not secure alone. In the absence of a social movement where people have the collective power to initiate change, abolishing this relationship would result in severe hardship, for me given that writing is not the most lucrative career.

We have a lot to learn from the past, especially as we consider whether or not to have a family and what kinship means. As I come to interview folk, read, and write, I see how most of us are shaped by what they inherit if they inherit anything. No single policy will solve the many problems plaguing our time—sexism, climate crisis, or austerity—but opening our imagination might give us more freedom as a society. What radical feminists offer us is the ability to question the world we inherited, more specifically, the uneven burden Western societies place on mothers to carry out child-rearing or the expectation that people form marital unions to legitimize their relationships.

I will always wonder what I have lost as a wife and mother and reflect on what I have gained. Although motherhood is fresh and slow, trickling into a stream of sleepless nights, I am witnessing a new being develop a personality, smile for no apparent reason, and grow. But more than anything, I will spend some time reading and reflecting on the type of elder I want to be, not just to my child but to all of the children who deserve care.

Writing

Driving through Florida this spring, I reveled in the lush sensory environment. Seven years ago, I left the United States for Germany, and amidst the dulling blandness of my adopted country, I had forgotten how much I yearned for the rich sights and smells of my home state. As I traveled from Miami to Gainesville, I was delighted by the flute-like humming of the scarlet tanager, the lanky sabal palm trees scattered across the eastern coast, the heretical rain pounding on my parents’ rooftop, and the peeping manatees poking their heads out of the water near the Gulf shore. I was thrilled at the fragrant cuisine—the citrus-infused seafood, fried plantains, juicy mangoes, and black bean stews. But passing through the Florida country roads, I was confronted, too, with churches and gun shops—reminders of why, in this place teeming with growth, it felt impossible for me to imagine making a life.

As I traveled through the landscape at once fertile and hostile, I found myself turning to Emily Raboteau’s book, *Lessons for Survival*, a collection of essays grounded in the author’s perspective as a mother raising children in New York City amidst the intersecting crises of anti-Blackness and climate catastrophe. Well into my second pregnancy trimester, I had hesitated to read Raboteau’s book. I dreaded encountering what I already knew: that I was more likely than white women or non-Black women of color to deliver a child prematurely, more likely to die from childbirth, and more likely to have my pain ignored by the medical professionals tasked with keeping me safe. I suspected the book would be a familiar self-help guide, instructing me on how to prepare a child for an impending natural disaster or dolling out tips for delivering «The Talk» about navigating racism. But when I finally picked up *Lessons for Survival*, what I found was not individuating advice that redoubled the burden on those already most vulnerable to premature death but an invitation to accompany a sweetly soulful ensemble of New Yorkers who, despite being bombarded with «an ominous sign for the Rapture» and stop and frisk policing, or otherwise internally displaced by the forces of capital, practice for a world where they could affirm their right to prevail. This sometimes-joyful, sometimes-painful insistence on forging a life where so much is arrayed against it echoed loudly as I prepared to bring new life into this world, traversing the landscape I’d left behind.

Throughout my pregnancy, I’ve been clouded by doubts about raising a Black child in a world where they will be misidentified, misperceived, and misunderstood. Nevertheless, I long for a red baby whose principles overpower the narratives that will try to break them—an anti-capitalist ecofeminist. And, given my six-figure student loan debt, the only things I can offer as a parent are my array of contemporary novels interspersed with Marxist literature. Like Raboteau, I want to orient my child (via books and literature) toward principles that soften some of the harsh material conditions of the world as an act of hope, a way to imagine—and, in so doing—to help bring a more life-sustaining future closer. «The pond is part of the place where we live (…). I observe the birds who stop there to bath: warblers, tanagers, grosbeaks, sparrows (…). Some of them are endangered. A small reparation: I am teaching our children their names.» Raboteau and her husband can accomplish this because of their work they have committed to honor their community’s natural life while acknowledging its fragility and resilience. By showing tenderness and care to other life forms, they see how the future of Black life is primarily bound to the preservation of the world…

You can read the rest of the essay in the Berlin Review.

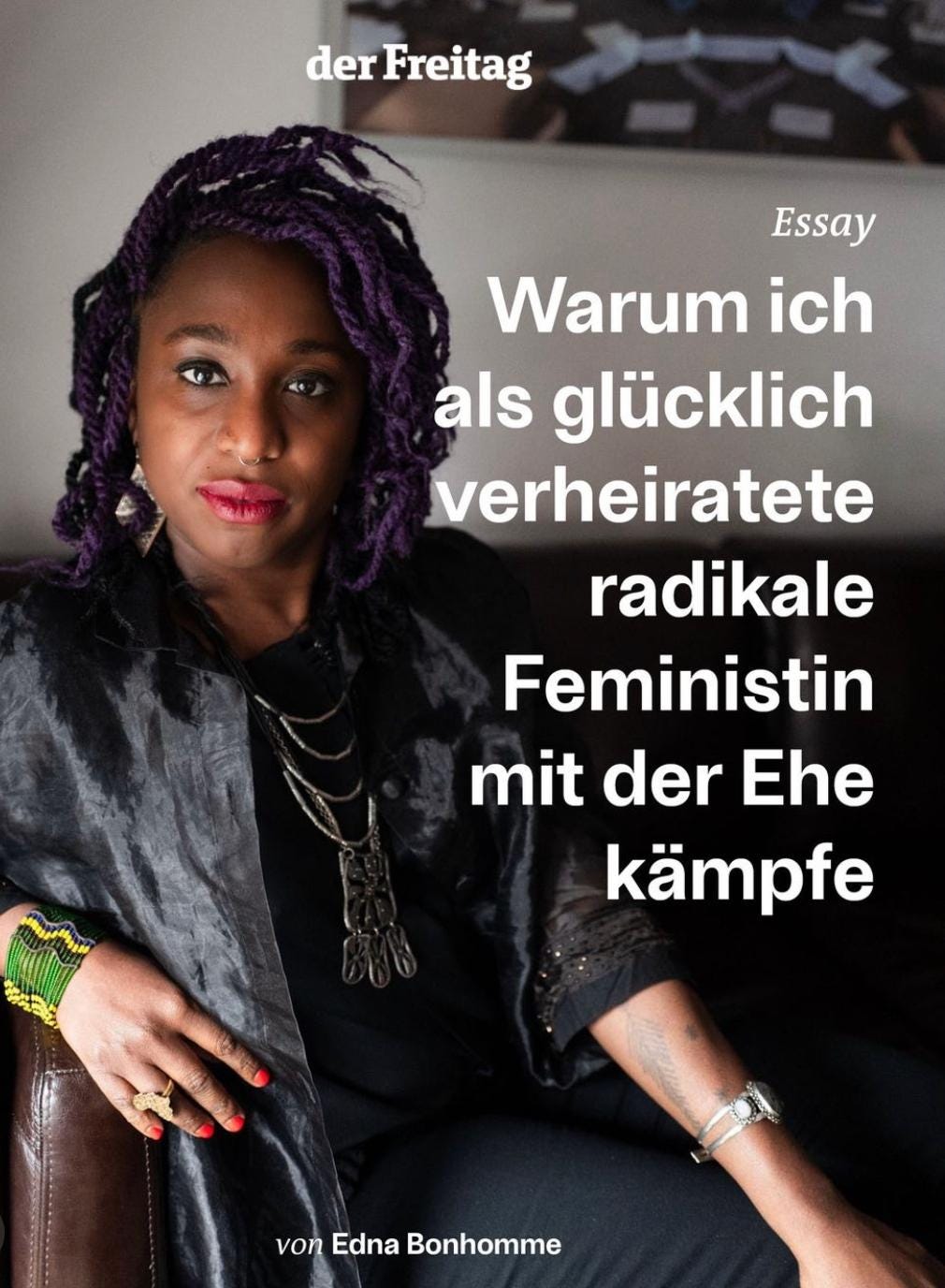

In case you’re interested in reading my book review, “Warum ich als glücklich verheiratete radikale Feministin mit der Ehe kämpfe,” about family and marriage abolition (in German), feel free to check out the essay here at der Freitag.

Closing Thoughts

Thank you all for continuing to read and engage with this newsletter. I will take a break from writing this newsletter until mid-September. Until then, I will work on slowing down, bonding with my child, and healing from childbirth.

As always, thank you for reading,

Thank you for reading Mobile Fragments. This post is public, so you can share it.

Congratulations on the new arrival and thank you for sharing this generous piece of writing. Your newsletters are always a joy to read.