“I wanted to engage the past, knowing that its perils and dangers still threatened and that even now lives hung in the balance.”

― Sadiyya Hartman, Lose Your Mother

Earlier this week, I re-read sections of Sadiya Hartman’s Lose Your Mother. In 2009, when I first discovered the text, I was living in Harlem, studying at Columbia, barely surviving, and always hustling. Hartman’s intellectual journey and fragmented familial history were her attempt to undo the erasure of her ancestors, to search for the intimate encounters of New World Blacks. As the progeny of African captives, our otherness is marked by the folks who survived the Middle Passage and chattel enslavement, people who excite a transient dial between joy and pain, with a splash of wretchedness interwoven with oracular dreams. Upon dismemberment in Ghana, Hartman discovered that her skin folk saw her as a “foreigner from across the sea.” A line had been drawn. Africans who never left the continent had moved on from recognizing us as their own, or rather, the ethnic groups that Hartman encountered had a new set of problems—the postcolonial ghosts of British imperialism—the vast continent that kept on growing. Different sets of traumas attended to the cultural separation and difference that made her feel like that far removed cousin awkwardly occupying a seat at the family table. As I re-read Hartman’s prose and absorbed the pain of knowing that we Black Americans are strangers in the country of our birth and aliens on the continent where our ancestors were stolen, I wept. I lamented for the dead I will never know and the living who never see me as their own.

I come from a people whose legacy cannot solely be reduced to enslavement and suffering, but whose collective existence is grounded on love, care, and respect. These are people whose living energies are flourishing in the lakou, while eating griot and listening to kompa. We play with Creole and celebrate the power and beauty of our sovereignty. Haiti and the Haitian diaspora are more expansive than its disasters; it is a place of liberation, of fashion and flare. Some of these images were taken directly in Haiti and others in Miami, and they all capture what it means to live beyond the parameters of mere survival.

Back in 2019, I had the pleasure of listening to Claudia Rankine read excerpts of her book “Just Us” in Berlin. I was engrossed by her grace, especially given that she is a deep thinker that slices through the discomfort of racism, a person who allows us to leap into our most intimate thoughts, a person who arranges poetic fragments, and someone who likes to walk behind strangers while overhearing their intimate conversations. Listening to her was like listening to the many Black aunties in the diaspora who teach us about resilience, laughter and love. She is graceful while echoing the calls of our ancestors and turning the mirror on the “Western” canon. She can go from citing T.S. Elliot to James Baldwin because she does the double labour that so many African diasporic people have been doing—knowing our traditions and theirs. I am especially elated by these moments when I can sit in the front row of an event that centres Black experiences because this stuff is for us and by us. Some of us find care in our solitude, mostly because it can give us the space to heal, reflect and forgive. We might need the seclusion to dissect our traumas and be generous to ourselves, to reflect on where we’ve come from and we hope to be.

What Have I Written

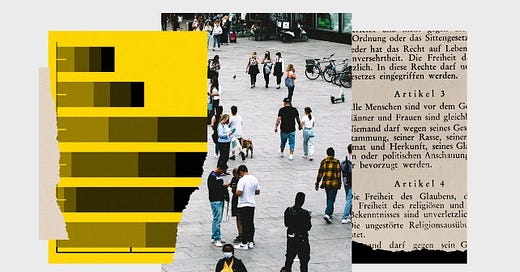

WIRED | What Germany’s Lack of Race Data Means During a Pandemic

I wrote an article for WIRED Magazine about the term “Rasse” (race), the 2020 Afrozensus, and the historical implications for documenting (health) data in Germany. I interviewed various Black activists & scholars to get their perspectives.

London Review of Books | Prejudice Rules

I am honoured to be part of this collection of brilliant writers reflecting on the overturning of Roe v. Wade including Elif Batuman, Rebecca Solnit, Sophie Lewis, Niela Orr, and more. Like so many people, the decision to remove federal abortion rights as we knew it, shook my spirit, leaving me with a sense of despair. But, writing and thinking alongside friends and comrades over the past two weeks has also reminded me that progressive feminists have been fighting, strategising, dreaming and gathering for ages. As Mariame Kaba notes, hope is a discipline that can allow us to gather the courage to fight. And as a historian, I am also reminded that hope can be found in the archives, in our activism, and in the seeds of history that reveal how progressives have unshackled their chains. We can awaken our reality by building a politics of freedom and bodily autonomy, without apology.

Still writing my manuscript Captive Contagions (One Signal/Simon & Schuster)

What Am I Reading

The long journey to thinking critically is also an act of reading widely. I’ve been really drawn to cultural criticism and the excellent work of scholars such as Sarah Chihaya’s book reviews and her collective project to write alongside other women writers. Beyond that, I am sitting with how novelists are reckoning with the environment (Helon Habila’s review) and how we can write queerness into children’s books (Winter). But more than anything, as I work through cultural science studies and how are we looking at the microbe (Osmundson) and the conscious state of being ill (Woolf).

Sarah Chihaya, Merve Emre, Katherine Hill, & Jill Richards | The Ferrante Letters: An Experiment in Collective Criticism

Helon Habila | Crude Reality

Tiya Miles | All That She Carried

Joseph Osmundson | Virology: Essays for the Living, the Dead, and the Small Things in Between

Jessica Winter | What Should a Queer Children’s Book Do?

Virginia Woolf | On Being Ill