Am I a cunt?

Coming to terms with why I am complicated, disparaging, and extremely disagreeable.

Once, while arguing, a male lover called me a cunt. I thought, I am not a cunt. But also, how dare he use such language, especially given that we stood, fully clothed, the word not serving as an instruction for fornication. Grated and agitated, this initial shock waned. By the time I was more composed, I asked him what his friends would think if they knew he called me a cunt. He confidently responded: “They would want to know the context.”

For a while, I was irked by his response because I knew some of his friends, and I guessed that a couple of the radical feminists would have disapproved of his portrayal of me. But then I realized that my stringent stare is quite intimidating, even though I stand only 156 cm. But more importantly, my ideas are just too fantastical, hysterical, or irrational. Having a conversation with me is like speaking to a brick wall that refuses to crumble from a wrecking ball. During that brief conversation, I didn’t raise my voice, curse at the man, or insult him. I just dissented, which is enough to rattle any male from such a maleficent being like myself.

But any deep thinker must look beyond a simple version of herself and question the origins and validity of someone else's critique. So I examined the meaning of the word “cunt” to see if there was any truth to whether this term applied to me. Am I a cunt?

The first definition was promising.

1. Vulgar Slang The vagina or vulva.

Because I have a vagina and vulva, I reflected on this term. I was reminded of Zambian writer and Professor of English at Harvard, Namwali Serpell’s essay in The New York Review of Books, “Black Hole. She highlights early on in her essay that Carl Linnaeus’s racial classification, which characterized Black people as the lowest human form, did so by describing a set of anatomical features, which he professed were associated with our alleged inferiority. Of those qualities, Black women’s genital flap, which he associated with “caprice,” could explain their mercurial temperament. Serpell uses satire and wit to unpack Western culture’s discomfort and obsession with Black women’s vaginas and writes:

Why would you want to drag Aryan pussy down to the bestial level of the negress’s free clitoris? This is the paradox of black pussy: it is bared, gazed at, dissected, used as a model—the literal textbook example, the “free, nonadherent” norm—yet so elided that it’s almost unGoogleable…

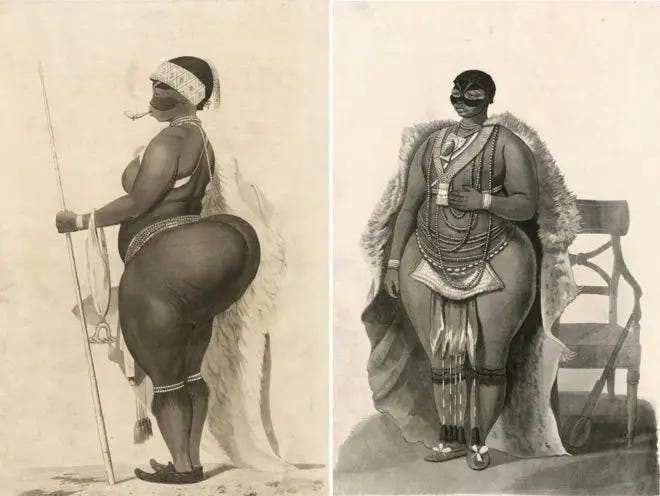

Both conspicuous and inconspicuous, the Black pussy is a phantom phenomenon to the point that European scientists have erroneously classified it, manipulated it, and even put it on display as a spectacle. Some people might be aware that Saartjie Baartman, also known as the Hottentot Venus, a Khoikhoi woman, was exhibited—even posthumously—throughout Europe in the nineteenth century. Sometimes, I wonder about the people who attended these shows. Were they motivated by curiosity, disgust, or both? Although this history is fascinating, I doubted that this lover’s use of “cunt” matched the pseudoscientific or physiological definition.

This is when I need to look further.

2. Vulgar Slang Sexual intercourse with a woman.

Hmm, when we had that argument, I didn’t think it was dirty talk or foreplay. But now that I realize where the conversation could have gone, I deeply regret not seizing the chance to be more salacious, to expand my mind, and to hook up with that person instantly. What a missed opportunity not to have immediately slept with the person who called me a “cunt.”

But alas, let’s proceed.

3. Offensive Slang

a. Used as a disparaging term for a woman.

b. Used as a disparaging term for a person one dislikes or finds extremely disagreeable.

This definition is more promising, and I am beginning to think that this is the cuntext* I needed. Without hesitation, I realize that, of course, I am extremely disagreeable. Anyone who has ever lived with me has probably experienced this during the many nights of communal whiskey drinking while chatting about Marx or revolution, or maybe when eating some of my homemade bread or cookies, or perhaps when they endured the strong cloud of me burning myrrh incense. Quelle horreur! But I digress. This is not what this male lover meant. They probably thought I was disagreeable in the way that other Black American women are considered. Here, Serpell offers more insight, but this time about the imperiousness that we Black women impose on the world:

There are many ways to be “difficult” in this world: stubborn, demanding, inconvenient, complex, troublesome, baffling, illegible. Black womanhood is where they overlap.

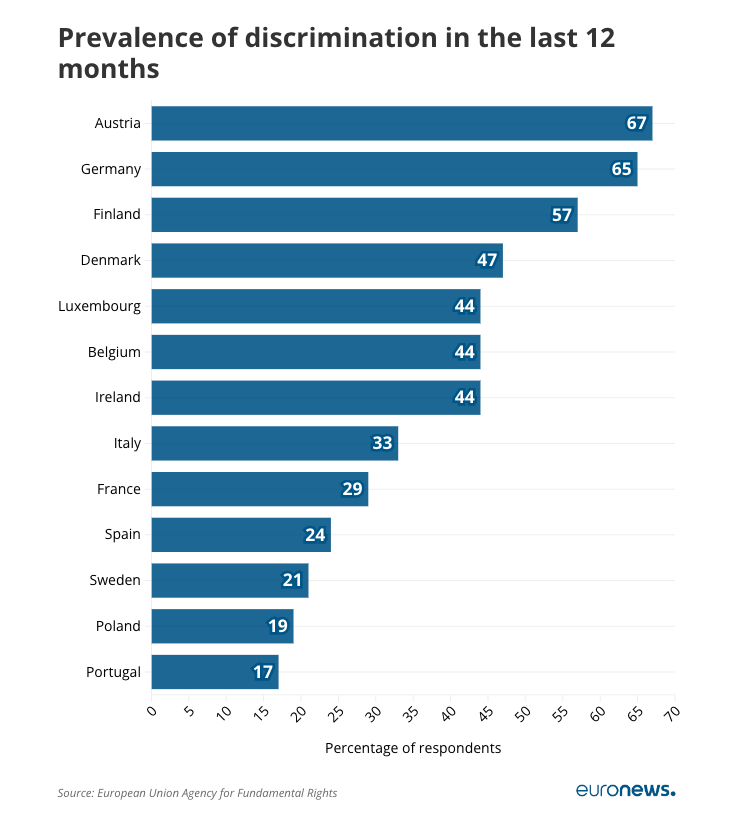

I believe I am all of these things, and more. But naturally, I had to consider why that might be. Maybe it’s because Black American women earn 66.5 cents for every dollar a white American man earns. Or perhaps it’s because Black American women carry more debt compared to white Americans. But the most striking fact is that the average life expectancy for Black Americans is 70.8 years, whereas for white Americans it’s 76.4 years. I know what some of you might be thinking, “Although you’re Black American, you live in Germany. It’s not America, and Europe’s not as racist.” Without delving too deep, some of you may be surprised to learn that racism is “pervasive and relentless” in Europe, to the extent that two-thirds of Black people in Germany have experienced some form of discrimination over the past year. [For those who want to read an extensive report on the matter, click here.]

There are many reasons to see me as a brusque woman—after all, I don’t display femininity with gentle ease or light tranquility. Maybe it’s because I don’t always smile, or perhaps because I don’t compliment everyone on their gaudy sweater. My disagreeable personality probably stems from another source of distress: ongoing rejection amidst the material constraints of living. I’ve been working outside the home since I was fourteen, taking on various odd jobs—including janitor, barista, tour guide, research scientist, Postdoctoral Fellow, editor, and writer. I work because I love learning. After all, I’ve made some incredible friends on the shop floor, and because I know that without socialism, I cannot rely on anyone for survival. I am difficult because I have questioned European colonialism, latent sexism, and the expectation that women should give up their careers to raise children.

More than many other groups of women, Black women are considered especially difficult as individuals. There are no racists who maintain racism, and there are no sexists who uphold sexism. Everyone seems to absolve themselves of the grave inequities we see and witness because they are not the most acute version of these systems, or maybe they don’t think their words or privilege have any power. The real problem is Black women, who continue to utter their disagreement, without packaging it in the most amicable form.

After receiving an austere and dismissive remark from a male art critic, Rizvana Bradley responded:

the habitual reflexes of the very discourse that would secure my annihilation, and certainly not as a clamoring to ascend to a “dais” that, in the eyes of civil society, can never be anything more or less than an auction block. Difficult, rather, in the sense that black women have always been difficult, have had to be difficult to survive, have borne the difficulty the world requires and abhors, the difficulty which perpetually haunts the world’s ceaseless churning.”

I am a prickly and surly person who refuses to be shackled by other people’s unacknowledged ideological chains. Looking at the data, I am starting to think maybe I’m a cunt.

Some Recommendations

Hamif Abdurraqib is a stellar essayist who reflects on Zohran Mamdani and Mahmoud Khalil

Elena Gosalvez Blanco worked for Patricia Highsmith near the end of her life

When I was a PhD student at Princeton and lived in Brooklyn, I spent hundreds of hours taking the bus on the turnpike. Read Simon Wu’s essay about the highway’s aesthetic

If you’re married, would your marriage survive if you were stranded in the ocean? Sophie Elmhirst wrote a brilliant book about a real-life situation where a married couple were stranded at sea

Please consider giving a positive review of my book, A History of the World in Six Plagues, on Amazon, Bookshop, and Goodreads. I would be grateful if you could recommend the book to people in your life, such as relatives, coworkers, pen pals, editors, or loved ones. You can post about the book on social media, in newsletters, or nominate me for a prize, etc.

Thank you all for continuing to read and engage with Mobile Fragments by Edna Bonhomme. This post is free, but if you enjoyed reading this, please share this newsletter with your family, friends, and others who want to keep up with my meanderings. Please consider becoming a paid subscriber if you’d like. Your support is appreciated, whether you are a paid subscriber or not. I occasionally post on Bluesky and Instagram, so feel free to follow me if you’d like to hear more from me.